Combining [ Video + GPS ] to Create Next Generation [ Online Maps ]

Pee Oui had struggled against the steep pitches on Mt Ventoux for over an hour in 2003. As he ground around another hair pin corner a curse barked from his dry throat, "You bastard, you killed Tommy Simpson, but you won't kill me."

Ventoux is the "Giant of Provence", a barren geological anomaly, an outlier of the Alps standing alone nearly twice as high as its surrounding forested mountain ranges, the Vaucluse, Luberon and Baronnies. There was never a good transportation need for a road up it. The poet Petrarch climbed it in the 14th Century and maybe that's why it was decreed. The road was used for logging that left the top naked to this day, but that was a one-way downhill proposition. It gives access to the grim tower of the weather station, but even that was abandoned many decades ago.

The weather. Ventoux is fairly close to the Mediterranean Sea. It is a mile high. Beyond are the Alps. Weather can change in a heart beat. Or not. In the 2000 Tour, when Armstrong and Pantani dueled, it was barely above freezing and the wind was up so high the finish banner could not be raised.

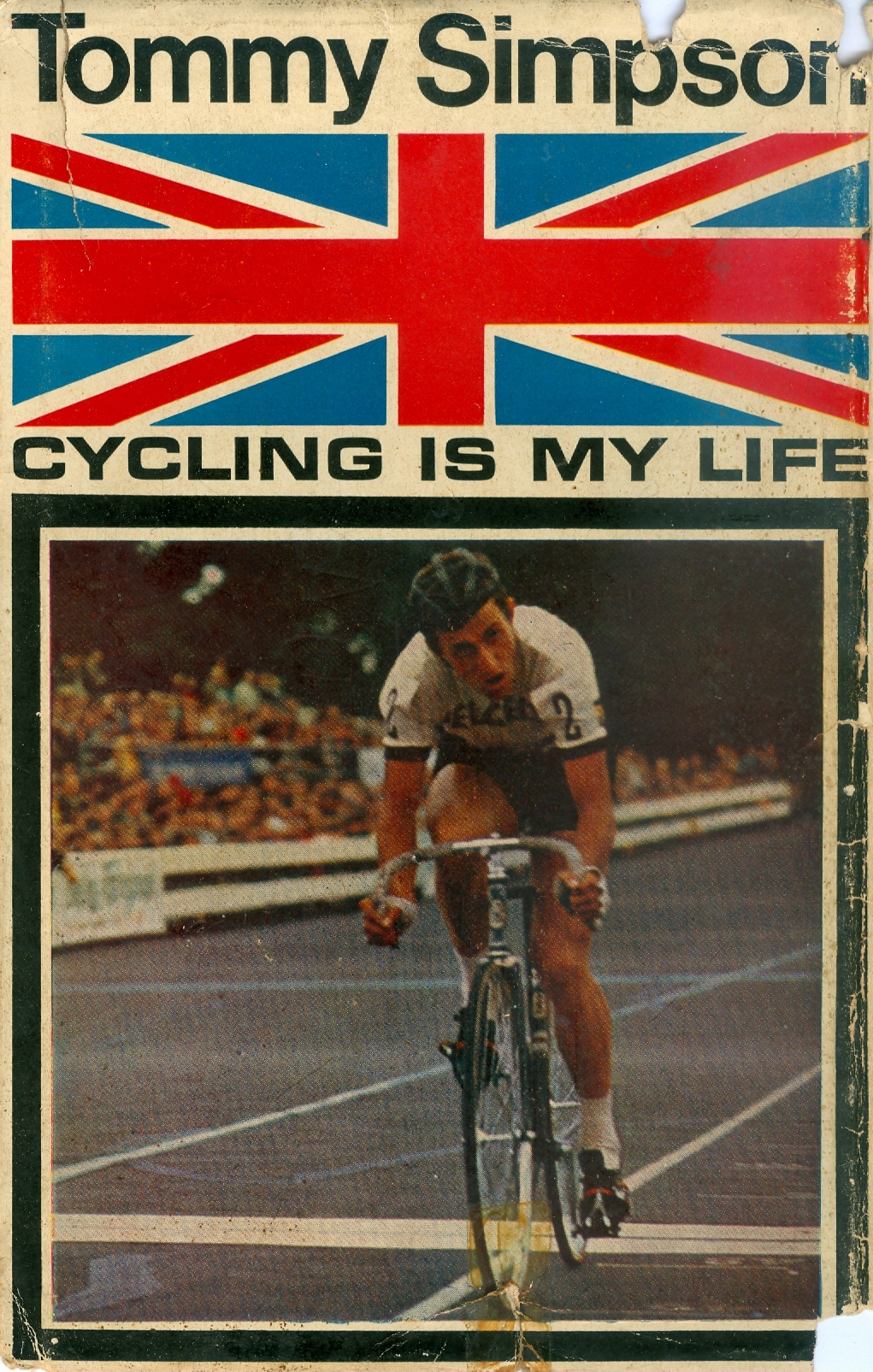

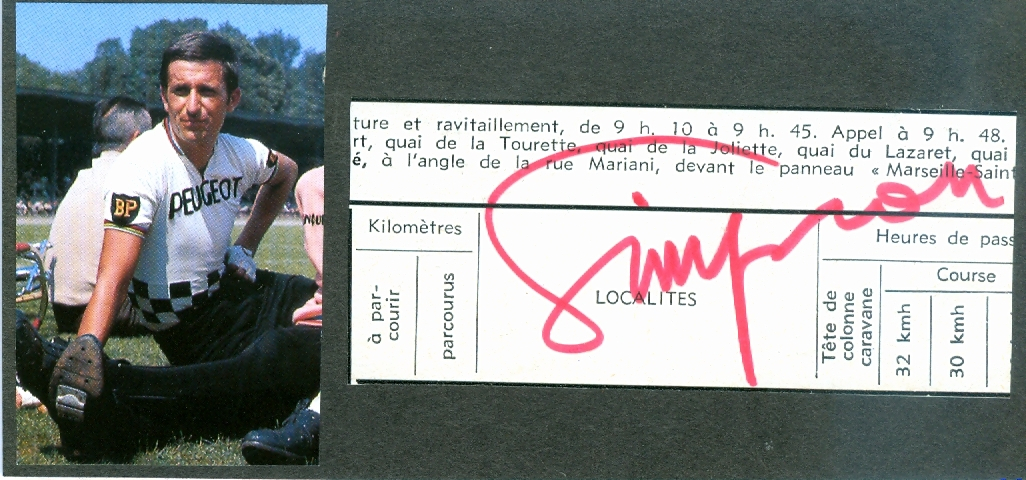

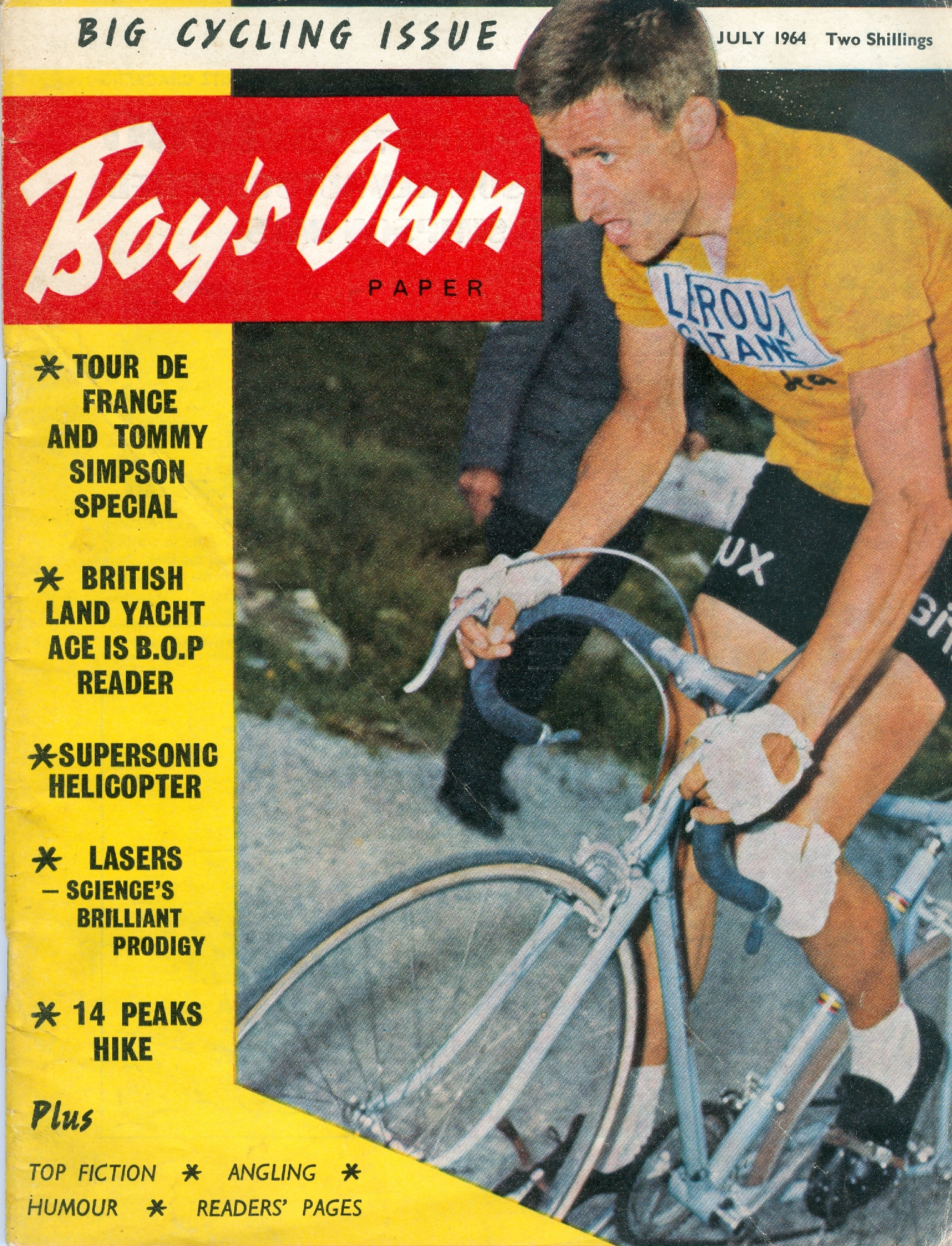

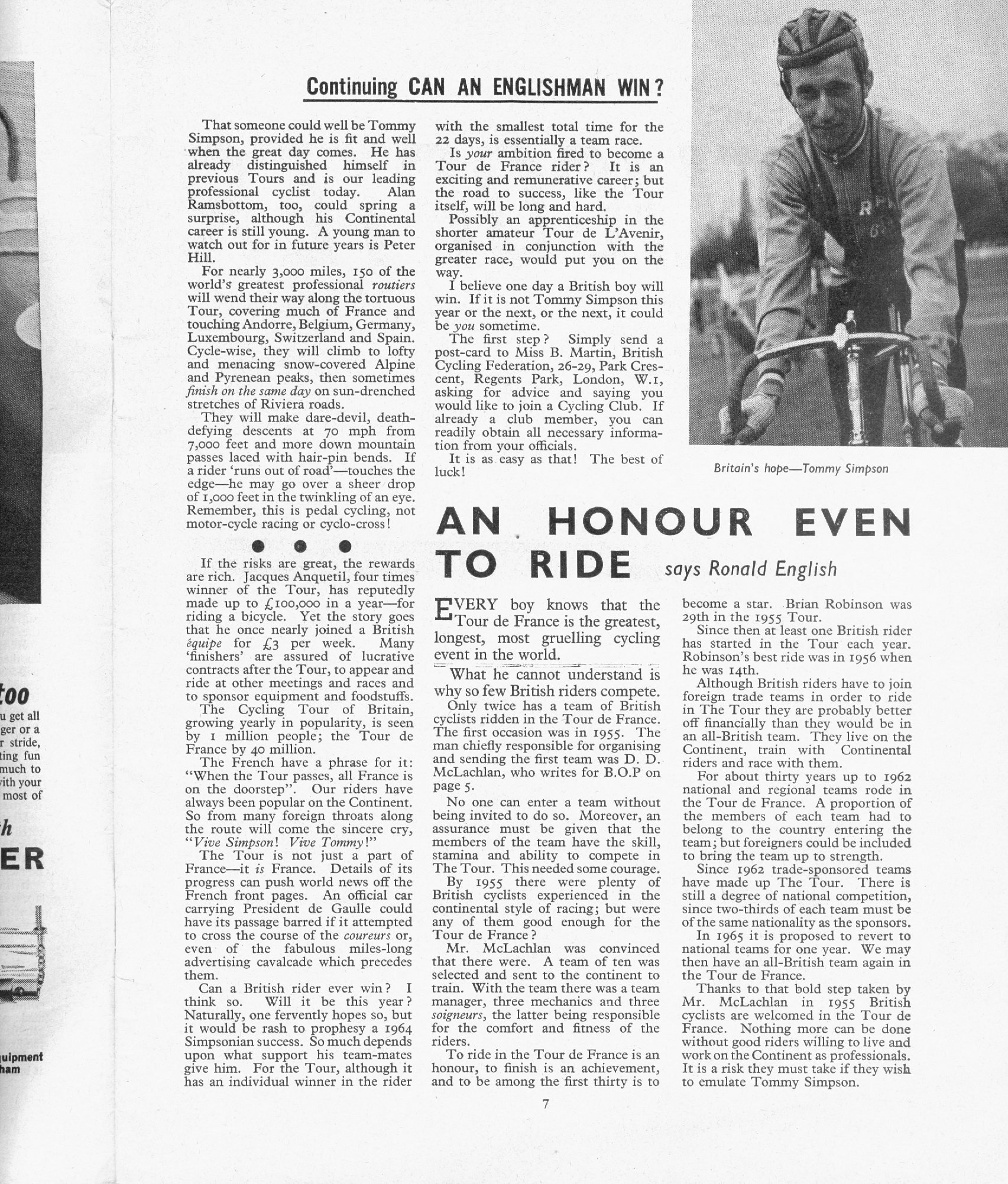

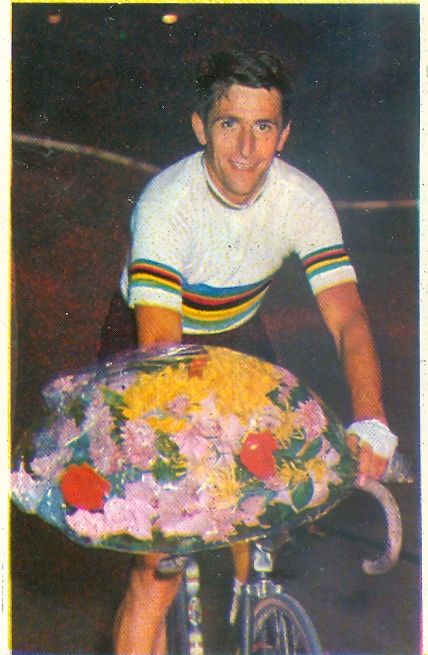

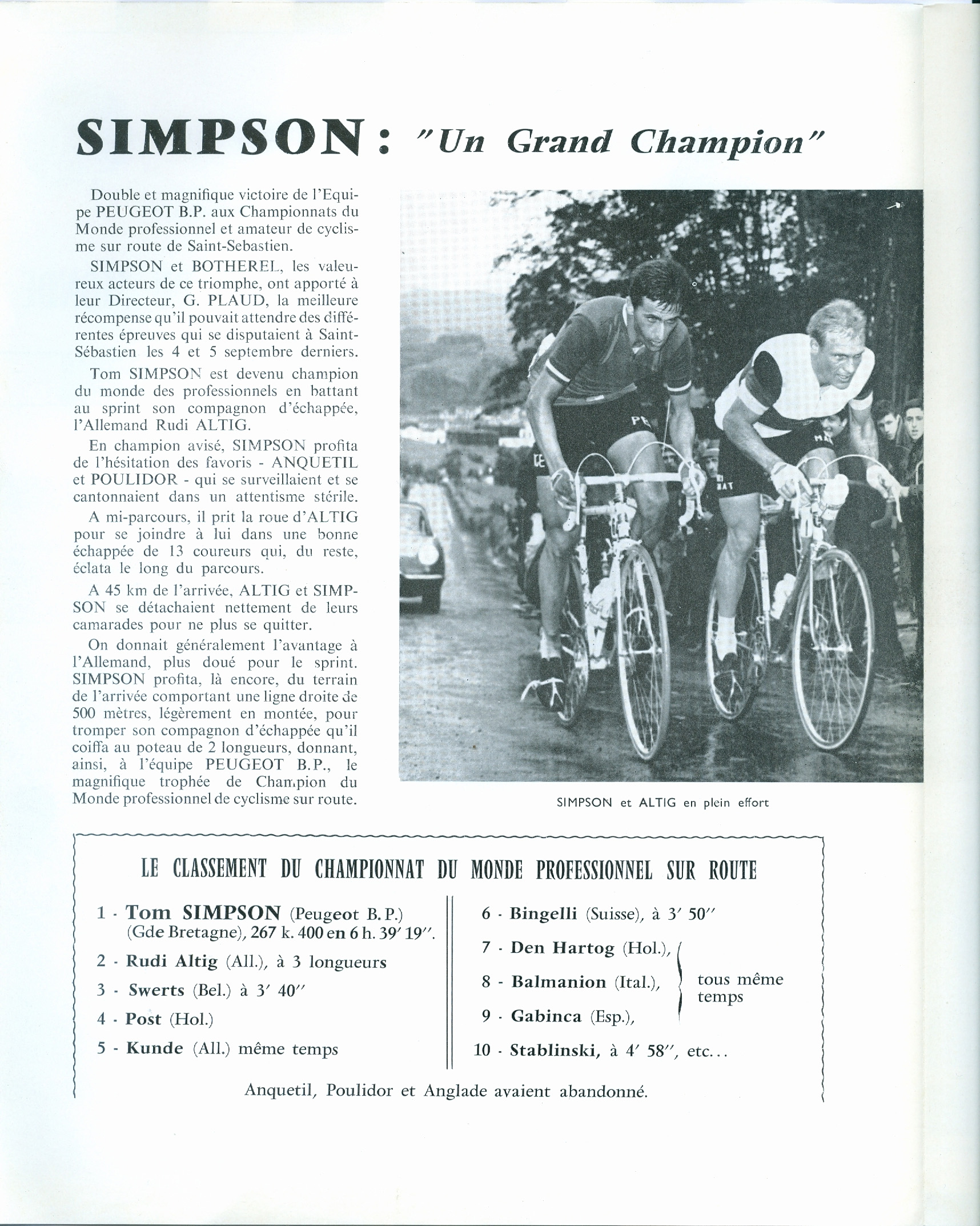

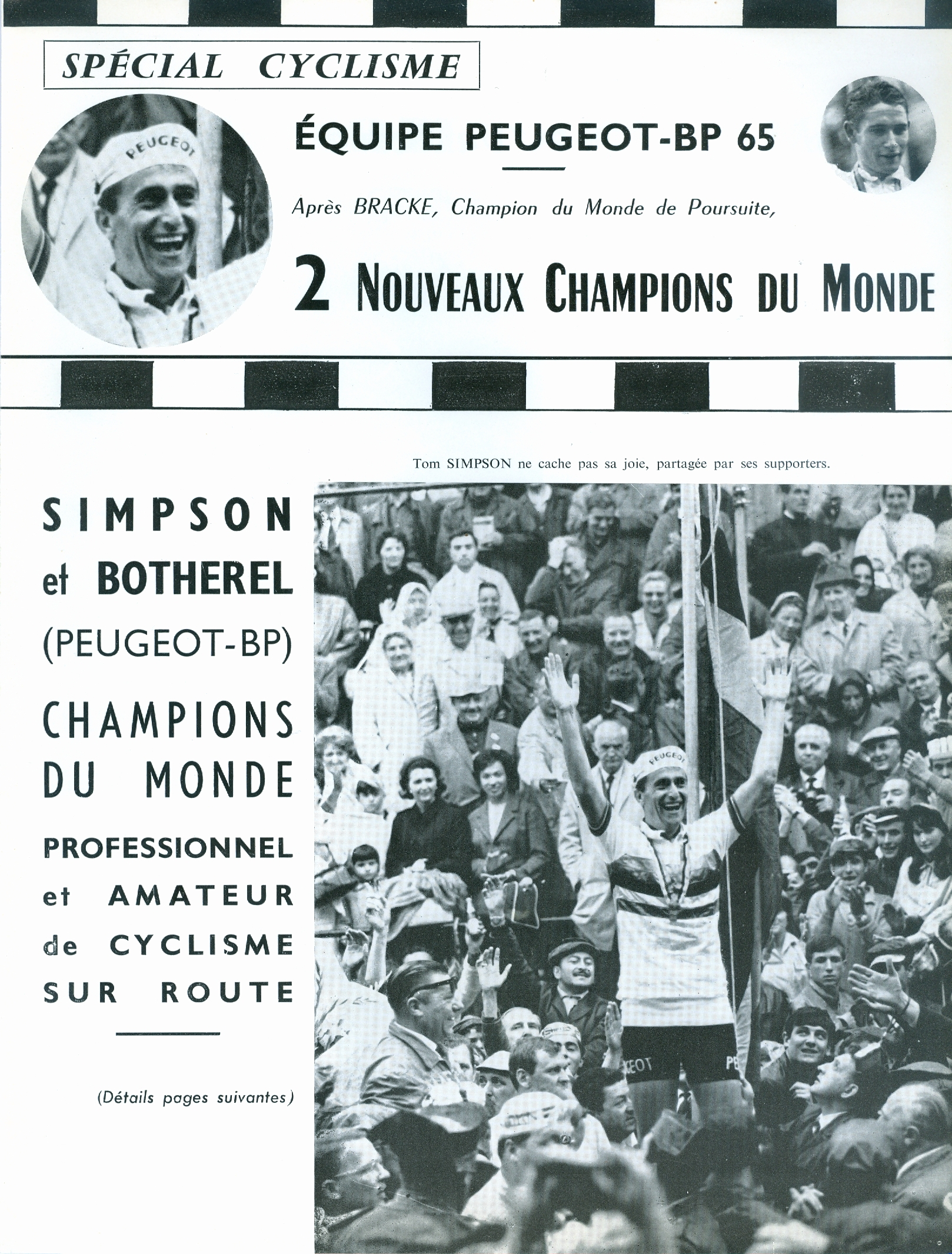

On July 13, 1967 it was ungodly hot. Maybe 120 degrees. Tom Simpson was laying seventh in the Tour. He had been the first Brit to wear the yellow jersey of Tour leader in 1962. "Major Tom" was World Champion in '65. He'd won three of the five "Monuments of Cycling", the Tour of Flanders, Milan-San Remo and the Giro d Lombardy, and the no longer run 350-mile Bordeaux-Paris. But, he said the greatest moment of his career was the one day he wore the yellow jersey.

In '67 on Ventoux Simpson was a desperate man on a desperately hot day. He needed to salvage his career. Bad luck had followed him. In the spring of '66, when he should have cashed in on appearance money as the reigning World Champ, he was recovering from an ankle broken in a skiing accident.

Scaling the 5,000 foot, 22 kilometer climb with the contenders, Simpson would fade so badly that the last year's winner, Lucien Aimar, would ask him if he was alright. He would make it out of the forest, onto the glaring white scree to within a couple Ks of the top before falling into the ditch still clipped into his pedals. His mechanic and the driver put him upright. He pedaled for a few hundred more meters. He fell again. Legend has it his last words were, "Put me back on my bike." He was 29 years old.

The Tour doctor was on Simpson quickly, but when the helicopter got him to the hospital in Avignon, he was already dead. The cycling world was in shock. An athlete of his caliber could push himself to the point of death. The shock expounded when the autopsy found amphetamines and alcohol in his system.

Simpson had been very popular. He had an vibrant personality and was always willing to ham it up for the fans and press. One famous photo had him sitting in a cafe in a spiff suit with a bowler hat, an umbrella in one hand, raising a cup of tea with the other.

Amphetamines were the drug of choice. They'd been rampant in cycling since WWII when Europe became awash with them as American troops liberated it on "pep pills." Unlike EPO or blood doping, it provided no actual performance benefit. It only made you believe you could do the impossible. Post Simpson-mort, five-time Tour winner, Jacques Anquetil said, "Every professional cyclist dopes and those who say they don't are liars."

The Brits were in denial. Years later a British cycling coach would say, "The only thing wrong with Tommy Simpson was he liked a little cognac with his coffee in the morning." The alcohol in his system was likely due to a raid on a bar near the base of Ventoux. Hand-ups weren't allowed and it was common practice for Tour cyclists to raid taverns for bottled water or alcohol. The organizers even had a system where bar owners could submit bills.

Simpson was buried in his native Yorkshire, where cycling had likely saved him from drudgery in the mines. The only pro cyclist at the funeral was this teammate Eddy Merckx. Eddy would not begin his five-win Tour effort for another two years. On his way to win number two in 1970, he did not miss tipping his cap and crossing himself as he passed the Simpson monument on Ventoux. British cyclists had raised the money for the memorial within a year of Simpson's death.

There are three ways up Ventoux. One is "easy" (lol) from Sault (which they pronounce "sew"). Only the last 6 K from Chalet Renard are part of race route. The traditional course is 22 K from the village of Bedoin. This is the route Simpson rode and the course this year. The way Pee Oui went was from the town of Malucene which is as tough, a hundred feet less but 21 K. Unlike from Bedoin, it starts out extremely steep. You turn a corner and are staring at a wall.

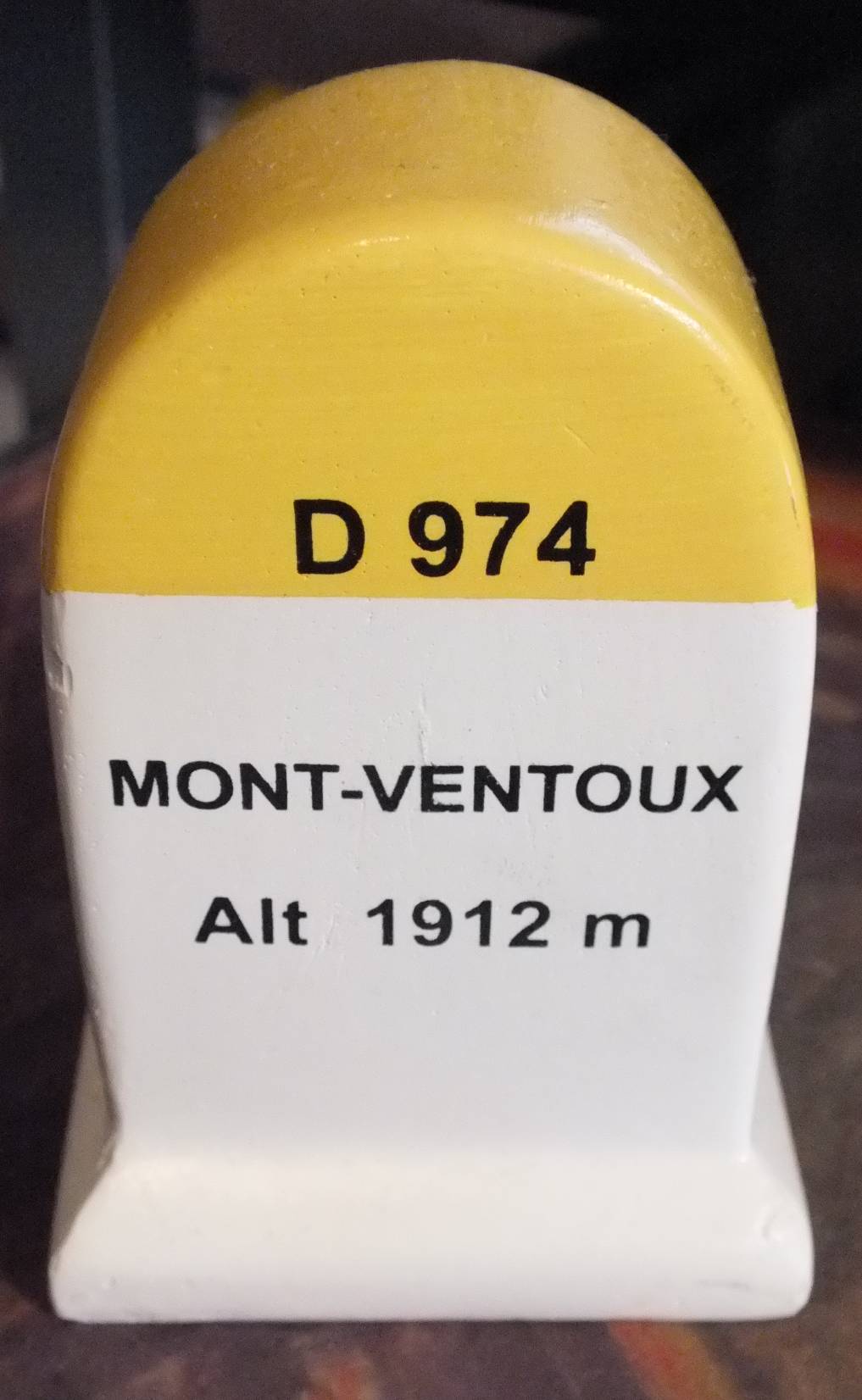

The diabolical thing about Ventoux is the grade is seldom constant. For good or bad, there are little tombstone-like markers at every kilometer which include the altitude and the percent grade for the next K. It was 90 degrees in the valley and Pee Oui was dressed accordingly in a light jersey. Five K up he decided he had to pee. The first of several stops. Quitting was never and issue (only a wish) as he had a rendezvous on the other side of the mountain and eventually the sun would go down.

It took everything to keep turning bottom gear. Then the weather changed. The wind came up. The temperature dropped. And, he was running out of water. Dark clouds swirled. The wind twisted like a tornado. Each K marker brought some solace, if 7% or less, or a groan, if 10% or more. There was nothing along the route. Nothing. A cafe at at turn to a ski resort wass closed. Pee Oui was tired, aching, and dry. He's only seen one cyclist and he was walking.

After his outburst about Simpson, Pee Oui got past by a cyclist with a smile on his face. Pee Oui was the pate' in his sandwich. On the open scree the wind was more fierce. It chilledthe sweat, but the struggle kept his core warm. He knew this wouls be a problem going down. Finally, rounding the last hairpin by the old weather tower where nothing, like water, appeared available, he came a across a family picnic at a pull out. They were Belgians. One was proud to show his Caterpillar cap, an American company he proclaimed. They had pity on Pee Oui and gave him water and newspapers to stuff under his jersey for the descent.

The newspapers help greatly, but the drop is steep, windy and very scary. Pee Oui misses the Tom Simpson memorial, but would not likely have stopped anyway. At Chalet Renard, also closed, he veered off on the road to Sault, a much gentler grade. Now he flew. He was out of the clouds pedaling or coasting at high speed, but without terror.

Nearing Sault he realized he must climb back up 300 feet to get to the village, so he turns south. For 23 K he pedals spinning his highest gear until a short uphill to a gap in Vaucluse Mountains.

Simpson was not the first to fall on Ventoux. In the 1955 Tour a French cyclist collapsed in the wicked heat. Ironically, the same Tour doctor who tried to save Simpson saved that cyclist. The Swiss rider, and 1950 Tour winner, Ferdi Kubler was riding Ventoux for the first time that year. Kubler, like Pee Oui, always referred to himself in the third person. Warned by fellow racer Raphael Geminiani to be careful, "Ventoux is not like other mountains", he shot back, "Ferdi not like other cyclists. France ready? Ferdi attack!"

Later, near the top, zig-zagging across the road, he was quoted, "Ferdi has taken too much dope. Ventoux killing Ferdi." Ventoux didn't kill Pee Oui or Ferdi. Kubler is the oldest living Tour winner at age 93 and is expected to be in Paris on the 21st for the finish where all winners except Armstrong have been invited. Pee Oui will ride the Champs Elysees with 10,000 other cyclists before the racers arrive. Simpson should have been so lucky.

Pee Oui returns to Ventoux this year, Alpe d' Huez and will ride the Champs Elysees with 10,000 other cyclists. Stay tuned for a report on his visit.